Environmental Determinants of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Pathways, Mechanisms, and Emerging Challenges

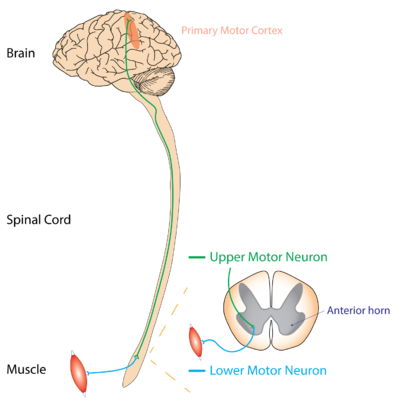

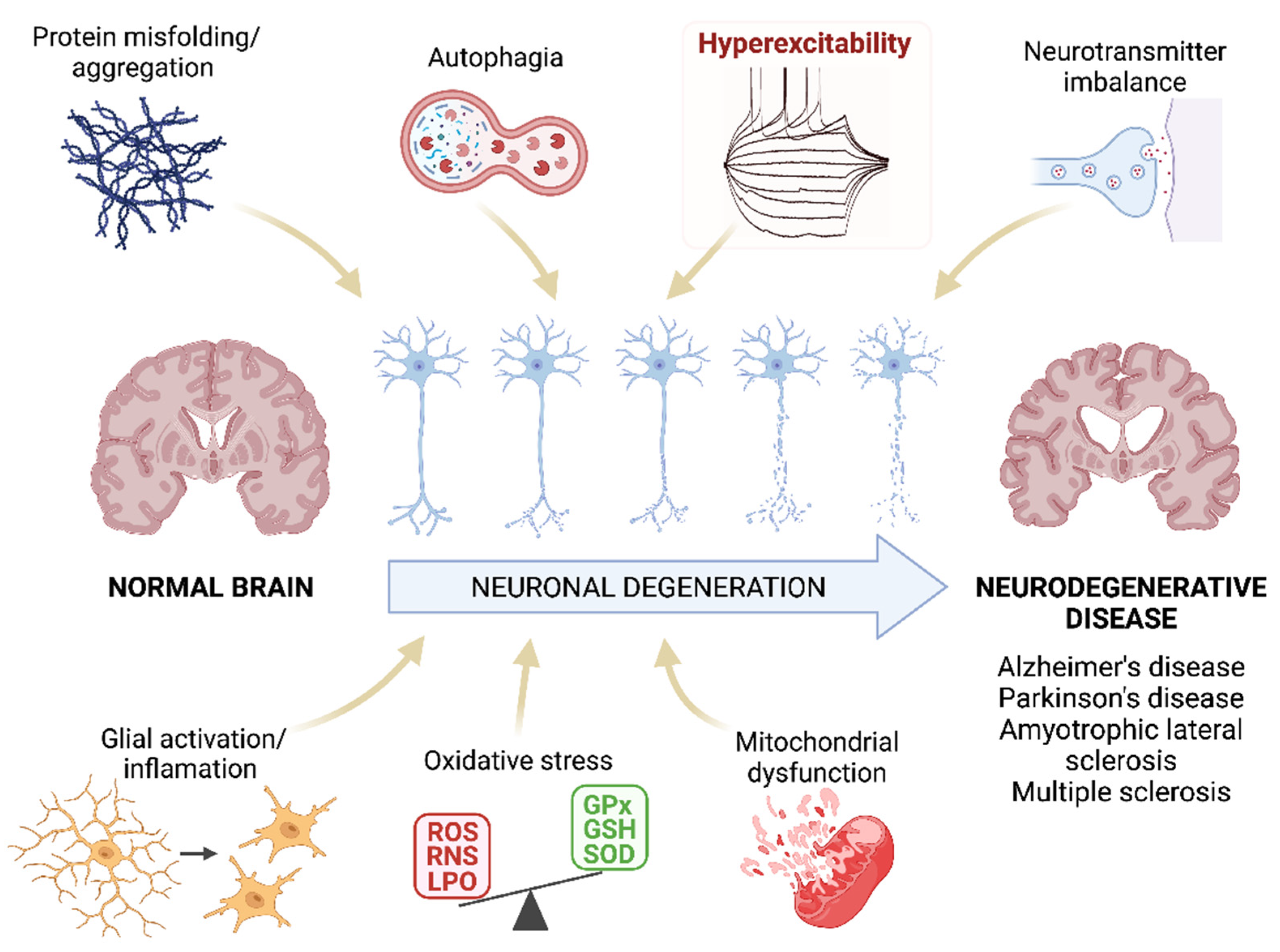

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. Clinically, it leads to muscle weakness, paralysis, and eventual respiratory failure. Traditionally, ALS has been framed largely as a neurological or genetic disease. However, this perspective fails to fully explain the epidemiology of the disorder.

Approximately 90–95% of ALS cases are sporadic, occurring without a clear familial or inherited genetic background. The predominance of sporadic ALS has shifted scientific attention toward environmental, occupational, and geographic determinants that may initiate or accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Increasingly, ALS is understood as a multifactorial disease, emerging from long-term interactions between environmental exposures and individual biological susceptibility.

Epidemiology and Spatial Patterns

ALS incidence varies markedly across regions, occupations, and environmental contexts. While the disease is globally rare, its non-random geographic distribution suggests that place-based exposures play a significant role.

Geographic clustering

Clusters of elevated ALS incidence have been reported in:

Industrial and mining regions

Intensive agricultural zones

Areas with documented air, soil, or water contamination

These clusters often persist across generations despite population turnover, indicating that environmental conditions rather than shared genetics may drive localized risk.

Occupational exposure patterns

Occupational groups repeatedly shown to have higher ALS risk include:

Farmers and pesticide applicators

Industrial and manufacturing workers

Construction workers

Military personnel

These occupations share chronic exposure to chemical toxicants, metals, solvents, and physical stress, strengthening the link between workplace environment and neurodegeneration.

Chemical and Toxic Environmental Exposures

Pesticides and herbicides

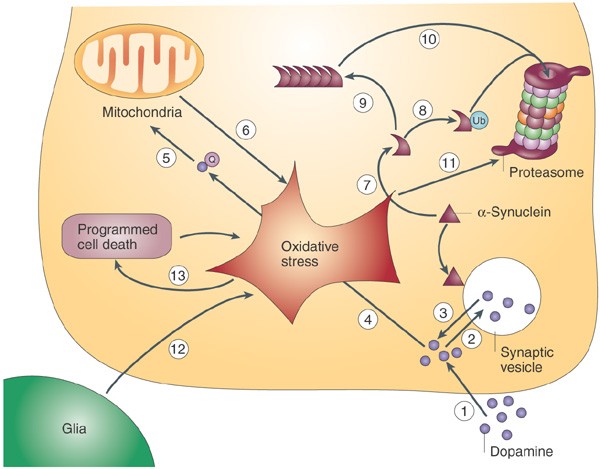

Among environmental risk factors, pesticide exposure has the strongest and most consistent association with ALS. Organophosphates, carbamates, and chlorinated pesticides are known to:

Disrupt neurotransmission

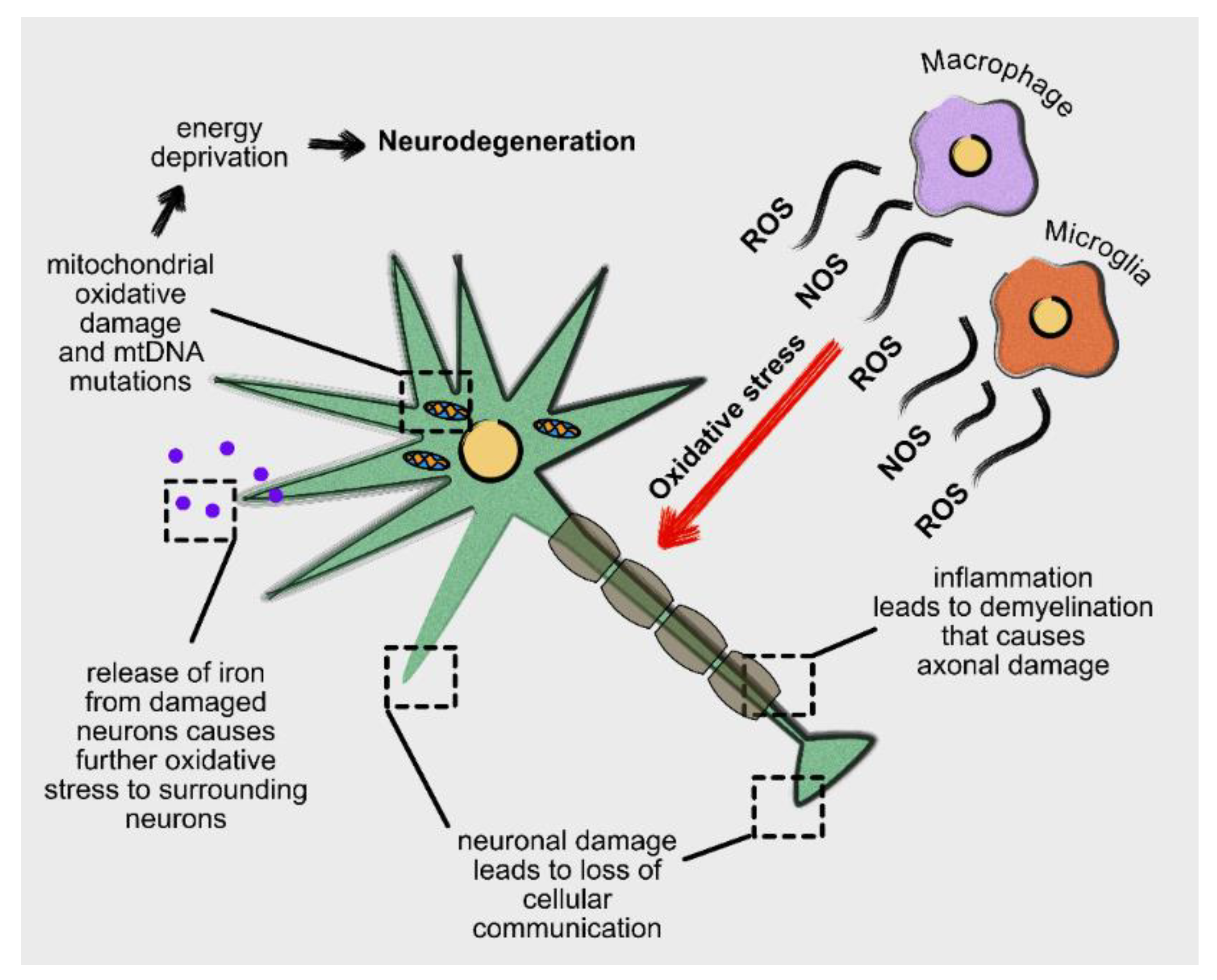

Induce oxidative stress

Damage mitochondrial function

Promote chronic neuroinflammation

Long-term, low-dose exposure—common in agricultural communities—may gradually overwhelm neuronal defense mechanisms, increasing vulnerability to degeneration.

Heavy metals

Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic accumulate in neural tissue and exert neurotoxic effects through:

Generation of reactive oxygen species

Disruption of calcium signaling

Impairment of DNA repair mechanisms

Elevated ALS prevalence has been observed near mining areas, battery manufacturing sites, and regions with industrial waste contamination.

Industrial solvents

Chronic exposure to solvents including formaldehyde, toluene, and trichloroethylene has been linked to motor neuron damage. These chemicals readily cross the blood–brain barrier and contribute to lipid membrane disruption and persistent inflammation.

Air Pollution and Neuroinflammation

Air pollution, particularly fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅), is increasingly implicated in neurodegenerative disease. Inhaled particles can:

Enter systemic circulation

Cross the blood–brain barrier

Activate microglial cells

Intensify oxidative stress

Long-term exposure to urban and industrial air pollution has been associated with earlier ALS onset and more rapid disease progression, highlighting air quality as a neurological as well as respiratory concern.

Cyanobacteria, Water Quality, and Neurotoxins

Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) represent a unique environmental risk through the production of β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), a neurotoxin linked to motor neuron degeneration.

BMAA:

Accumulates in freshwater and marine ecosystems

Enters food chains via fish, shellfish, and crops

Can be misincorporated into neuronal proteins

Regions experiencing frequent algal blooms have reported elevated ALS incidence, underscoring the role of water quality, eutrophication, and ecosystem disruption in neurological health.

Physical Stress, Trauma, and Occupational Load

Environmental risk does not operate solely through chemical exposure. Physical stressors may increase neuronal vulnerability, particularly when combined with toxic environments.

Factors associated with increased ALS risk include:

Repeated head injuries

Intense physical exertion

Military combat exposure

These stressors may accelerate neurodegeneration by increasing metabolic demand and inflammatory responses in already stressed neural systems.

Gene–Environment Interactions

Environmental exposures alone do not explain all ALS cases. Increasing evidence supports a gene–environment interaction model, in which environmental stressors activate latent biological vulnerabilities.

Environmental agents may:

Alter gene expression through epigenetic modification

Impair cellular stress-response pathways

Accelerate neuronal aging

This framework explains why ALS often appears later in life and why individuals with similar exposures experience different disease outcomes.

Lifestyle–Environment Overlap

Lifestyle factors do not independently cause ALS but may modify environmental risk.

Smoking

Smoking introduces heavy metals and oxidative agents that may amplify the neurotoxic effects of environmental exposures.

Dietary pathways

Contaminated food represents a significant exposure route:

Pesticide residues on crops

Heavy metals in fish and seafood

Algal toxins bioaccumulated through aquatic food chains

Chronic dietary exposure results in low-dose neurotoxicity that accumulates over decades.

Alcohol

Alcohol may function as a disease modifier by impairing detoxification pathways and increasing oxidative stress, rather than acting as a direct cause.

Soil and Groundwater Contamination

Soil and groundwater act as long-term reservoirs of environmental toxicants, particularly in rural and agricultural regions.

Persistent pesticides remain in soil for decades

Crops absorb metals and chemical residues

Groundwater contamination with arsenic and industrial effluents exposes entire communities

Chronic ingestion of contaminated water is a plausible but underexplored contributor to long-term neurodegenerative risk.

Climate Change as an Indirect Risk Amplifier

Climate change does not directly cause ALS, but it intensifies environmental exposure pathways.

Rising temperatures promote harmful algal blooms

Heat increases chemical toxicity and absorption

Shifting agricultural practices alter exposure profiles

Climate-driven ecological changes may therefore expand populations at risk and complicate disease prevention strategies.

Limitations and Scientific Uncertainty

Despite strong associative evidence, several challenges remain:

Long disease latency complicates exposure assessment

Reliance on self-reported exposure histories

Difficulty isolating individual toxicants from complex mixtures

Most findings remain associative rather than causal, and ALS heterogeneity further complicates risk modeling. Acknowledging these limitations strengthens scientific rigor and highlights the need for integrated, multidisciplinary research.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is best understood not as a purely genetic or neurological disorder, but as the outcome of lifelong environmental interactions with vulnerable biological systems. Chemical pollutants, air and water contamination, occupational stress, lifestyle modifiers, and climate-driven ecological changes collectively shape ALS risk.

Viewing ALS through an environmental lens reframes it as a place-based public health challenge, demanding responses that extend beyond clinical care to include pollution control, occupational safety, ecosystem protection, and environmental justice.

In revealing how environments silently influence neurological survival, ALS research offers critical insight into the broader relationship between human health and the integrity of the environments we inhabit.

Comments

Post a Comment